Earlier this week, the Wall Street Journal reported that merchants like Home Depot, Target, and Amazon are becoming increasingly frustrated with the high fees they pay to accept rewards credit cards, and are seeking relief from the courts or through negotiations with Visa and Mastercard. Particularly, merchants are looking for the networks Visa and Mastercard to end their ‘honor all cards’ rules, which say that if you accept any Visa credit card you need to accept all Visa credit cards, and ditto with Mastercard.

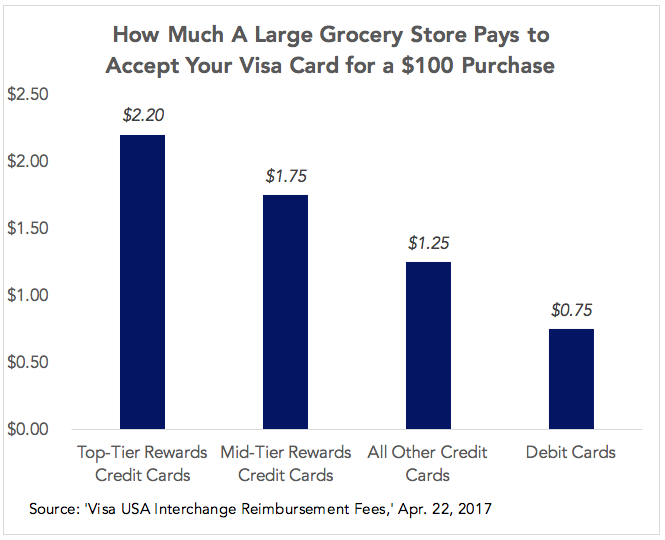

Today, if you spend $100 at a large grocery store, Visa would charge the store a $2.20 processing fee if you used a top-tier rewards credit card from their Visa Infinite line (like Chase Sapphire Reserve), a $1.75 fee you used a Visa Signature rewards credit card (like the Bank of America Travel Rewards Card), and $1.25 fee for any other Visa credit card, which are generally those without rewards. By comparison, to accept a debit card, the processing fee would be 75 cents or less.

The article points out that rewards credit cards are incredibly popular with consumers – but do consumers actually win in the current system where merchants pay a fee to the networks (Visa, Mastercard, Amex and Discover), the networks pay issuers (Chase, Citi, Capital One, etc.), with much of the final fee getting sent back to customers in the form of rewards?

On the surface, the Americans who avoid paying interest on their credit card by paying their bill in full each month are getting a great deal – a family spending $1,000 per month on their credit card can easily net $200 per year in “free cash” from rewards. Beneath the surface, things get more complicated.

A regressive system

The most obvious flaw with the current system of processing fees and rewards is that stores raise prices to cover the fees – and because giving out a 1% or 2% percent discount to people who are paying with cash or a debit card can be clunky, those prices are usually higher for everyone, not only those paying with a rewards credit card. On balance, that system is regressive, given that the Americans who primarily shop using their credit card are wealthier than the Americans who primarily shop using cash and debit. Researchers at the Federal Reserve of Boston found that because of the price effects associated with credit card rewards, the lowest-income households, those that make $20,000 or less annually, pay an extra $21 per year in higher prices, and the highest-income households, making $150,000 or more annually, receive an extra $750 every year in rewards.

It was with these prices effects in mind that Australia and the European Union both passed rules limiting credit card processing fees to less than 1%.

But there’s another, more subtle, reason why credit card rewards may not be the boon to consumers that they’re made out to be.

Confusing the shopping experience

While some consumers use credit cards purely for the rewards and convenience, 60% of active credit card users are “revolvers” who borrow money and pay interest on their credit cards.

For consumers that are going to borrow money using their credit card, picking out their credit card based on the rewards is like buying a house because you like the color they painted the bedroom – it just really shouldn’t be the most salient feature.

Credit card interest rates vary significantly – for customers with the best credit scores, Discover, BarclayCard and Capital One offer APRs as low as 13.74%, while subprime customers can expect to pay upwards of 25%. That 12 percentage point spread is pretty significant when you consider the best credit card rewards hover around 2%. And because interest compounds, the difference can become even more significant.

Consider a customer with a good credit score who spends $3,000, and pays off $100 each month. At a 13.74% interest rate, they’ll pay $696 in finance charges. Raise that rate by one percentage point and their finance charges will go up by $69. Raise it by 2%, and the charges go up $141, landing at $837 paid to borrow $3,000. By comparison, their rewards on that spend would have only been $60.

TV advertisements and popular comparison websites like CreditKarma and CreditCards.Com, paid by the banks to advertise their products, focus almost exclusively on rewards and perks, at the expense of comparing interest rates and fees.

This has been a meaningful shift over the last ten years. The 2017 CFPB Consumer Credit Card Market Report found that while in 2002, only 20% of credit card mail solicitations advertised rewards, today, roughly 60% do.

In a world without credit cards rewards and perks, issuers would start competing again on interest rate, drawing people’s attention back to where it should have been all along. The graph below pretty clearly shows how U.S. consumers focus has drifted – in 2004, Americans Googled credit card APRs and credit card rewards at a similar rate, while in 2018, credit card reward searches were more than three time as common.

Much of the change here has happened at the subprime end of the market, where consumers are the most vulnerable, and the least likely to pay their credit card bills in full. In the three years between 2011 and 2014, the percentage of new subprime credit cards offering rewards rose to 58%, up by 37% points.

A “shrouded equilibrium”

Mary Zaki, an economist at University of Maryland, has called the current credit card market a “shrouded equilibrium,” noting that lenders can avoiding competing on price because consumers have so much difficulty assessing how an interest rate translates into the cost to borrow.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that consumers would prefer to think about and compare based on rewards, which are ‘fun,’ compared to fees and finance charges, which are painful.

Some academics and experts, like Lauren Willis, Professor of Law at Loyala University, have proposed that regulators require credit card companies to start using ‘Smart Disclosures.’ While standard disclosures like the famous “Schumer Box” are a table of key terms, a ‘Smart Disclosure’ would leverage each consumer’s own pattern of purchases and payments to predict the total amount of fees, interest, and rewards that person would accrue. There’s a lot to like about those proposals – but we might be better off in a world where most financial products were just simpler to begin with.